Chris Darby

Chris Darby, a retired paramedic superintendent, served in EMS in London, Ontario, for 45 years. Chris was involved in fleet services and occupational health, chairing the committee for employees and management. Following retirement, Chris compiled his years of stories and anecdotes about his work in EMS into a memoir, publishing Running Reds in 2021.

Paramedics, once referred to as mere “drivers,” have been the architects of the evolution of ambulance design. Their relentless pursuit of improved patient care, a priority that emerged decades ago, has led to significant advancements. The vehicles we use are not just modes of transportation but the tools that connect our care to the patient and the further attention that awaits at the end of their journey. Horse-drawn ambulances, with their attendant tales, are a testament to the rich history of our profession. As our specialty moves forward, so do our vehicles, not just in model years.

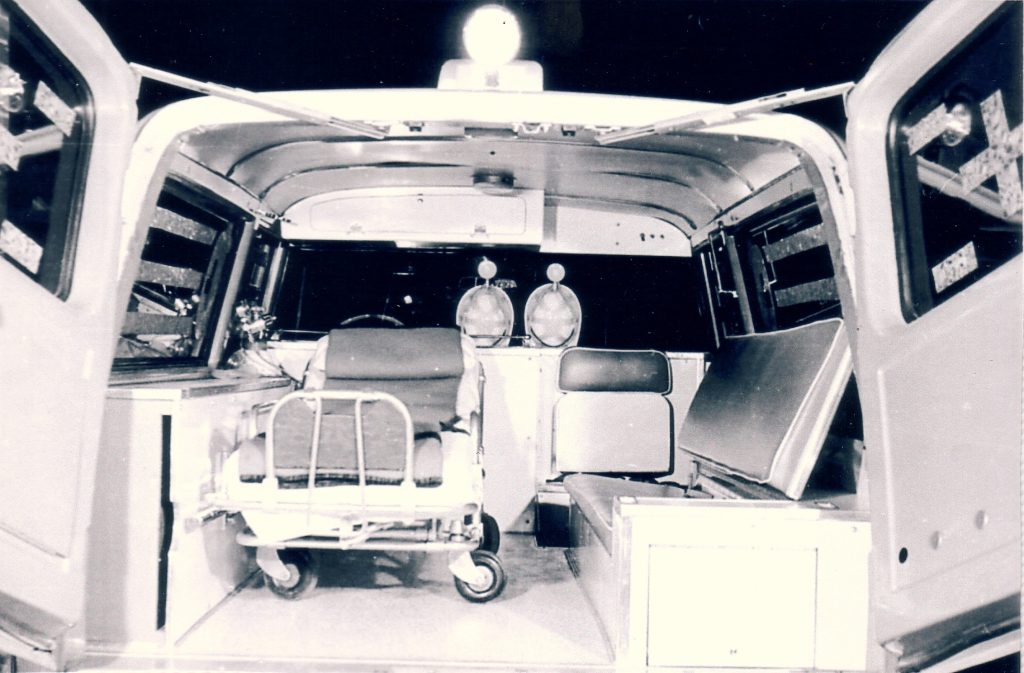

In the early years of my career, local ambulances serving London, Ontario, were born in the late sixties. New units arrived annually during my forty-five years. The earliest CPR standards were hindered by SUV models that lacked headroom in the patient compartment. Some stretch ambulance models offered four patient positions, and three required army-style stretchers not carried in the vehicle. It was a time when the note on the taxi window read, “One or four, you pay no more.” These challenges, though significant, have paved the way for the remarkable progress achieved today, a testament to the resilience and ingenuity of our profession.

Our shared concerns about safety and roadblocks to better patient care led to essential changes. Government administrators and safety inspectors were crucial in improving regulations and standards, which expedited ambulance design when shared with emerging manufacturers. Attempts to provide the first two stretcher units using standard low-rise vans created new problems, including crew seating and the paramedics’ movement in the patient compartment. However, these challenges were overcome through our collective efforts, a testament to the power of collaboration. Demonstrating patient care to the people who would change the standard forged new ideas with improvements patients deserved.

Raising the issue was not enough initially to make the point. Innocent and ambitious, I starred in a brief Beta-format video (boy, does that make me feel old) demonstrating the limitations of paramedic movement while caring for patients. Meetings to share the message from our committee with the key groups that could implement needed changes paid off for paramedics and patients.

Our province set the mark for standardizing ambulance design through legislation, centralized purchasing and distribution. In the mid-80s, Type II vans with raised roofs arrived, improving CPR performance. Shortly after the extended roofs hit the street, our first Type III modular two-stretcher ambulances arrived, with interiors designed for paramedic performance and safety. The Crestline Sprint had landed.

It was the new millennium, and the face of EMS changed again. Using established legislation, communities in Ontario were now responsible for replacing their ambulances. Quicker than you can say trauma, the 2000 Crestline Fleetmax Type III single stretcher ambulances arrived in Middlesex County. Designed with a larger patient compartment and improved lighting inside and out, paramedics enjoyed the newfound options, giving them more flexibility and added safety while caring for their patients. Features in the cab, “the office,” including added storage and the latest accessory control console, made medics more tolerant of the long hours on the road.

Paramedics proposed an improvement in a cooperative approach compared to past changes. Interior door safety handles occasionally failed with the challenges of entering and exiting units using the handles to steady up. Always in a rush and often carrying heavy equipment, the improved handles were a lifesaver. New vehicles arrived in 2003 with robust yellow grips for medics’ safety. The continuous product support was a bonus, assisting with retrofitting the existing fleet. Falls in and around the ambulance became a thing of the past.

A routine that drew attention was the exchange of large oxygen cylinders now positioned in an outside compartment. Removing them from the squad bench after decades was an overnight improvement. Around 2007, the revised loading process arrived in the Fleetmax exterior compartment, with a ramp and a dedicated wheeled bracket to fasten the tank to ensure a secure cylinder.

Bariatric patients are a challenge for all paramedics. Additional assistance at a scene is not always an option; that’s when technology intervenes. Electric lifts to assist patients into the patient compartment have reduced workplace injuries and improved the patient’s experience during an emergency. Moving the stretcher mounts away from the wall also made the medic’s job easier. Our bariatric ambulance arrived in 2014.

The priority of improved vehicle design ranks closely behind the changes in the approach to patient care. Evidence-based modifications between the two have earned some interdependence, one often affecting the other. The foundation of the pre-hospital industry, including paramedics’ skills and vehicles, evolved throughout my career, demonstrating to the author that progressive individuals drive our craft. Both groups, the caregivers and the professionals building our ambulances, are bent on improving patient outcomes and the working conditions for professionals serving them. Though I retired from pre-hospital care, my curiosity drive has not waned. What advances are just around the corner?